NL-GHK-Cu peptide therapy stimulates regenerative processes, thereby promoting the reduction of scars of various etiologies and inhibiting the risk of developing these cutaneous changes.

Abstract: NL-GHK-Cu is a tripeptide with the amino-acid sequence glycyl-histidyl-lysine and occurs naturally in human plasma. It is regarded as a potent reparative and regenerative peptide. NL-GHK-Cu exhibits a multifaceted biological activity profile, stimulating processes that help prevent scar formation while also reducing established scars of diverse origins and causes.

Keywords: skin; exposome; hydrolipid barrier; NL-GHK-Cu; wounds; skincare; tissue remodeling; scar

Introduction

As a signaling peptide, NL-GHK-Cu consists of three amino acids—glycine, histidine, and lysine—structurally complexed with copper. Copper binding is particularly important because many human enzymes cannot function properly in its absence. Copper is a cofactor for numerous enzymes, including the key antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). NL-GHK-Cu promotes highly effective regeneration of damaged skin, including scars of various etiologies, visibly attenuating existing scars and limiting the formation of new ones.

Skin Structure

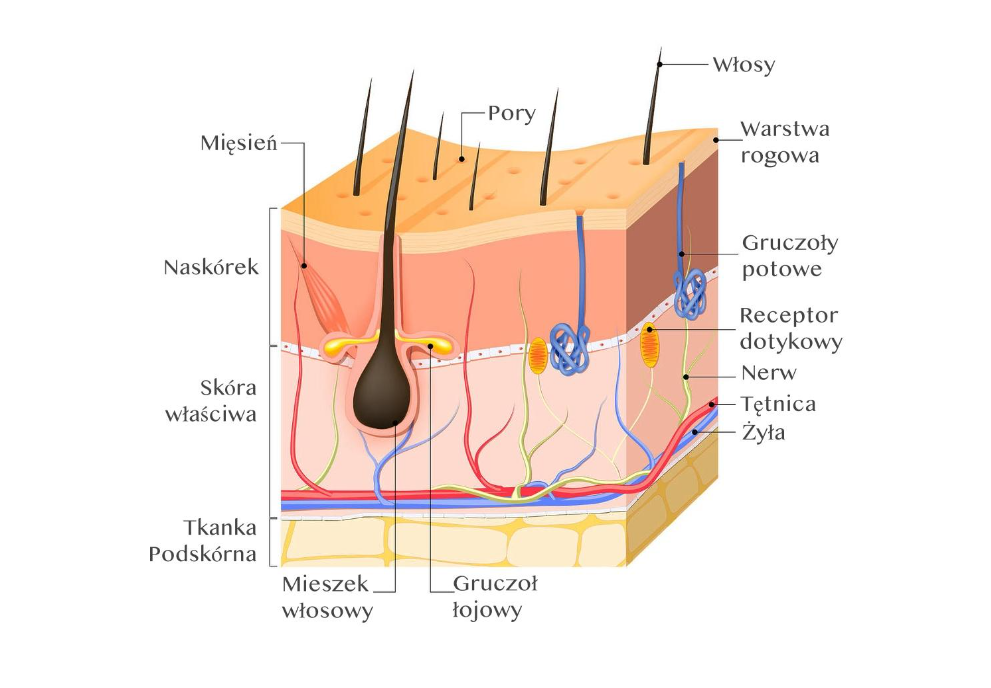

The skin is the largest organ of the human body, and its condition often reflects overall systemic health. It is composed of three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous tissue. The epidermis—the outermost layer—includes the basal, spinous, granular, lucid, and corneal layers. It lacks blood and lymphatic vessels. The dermis comprises the papillary and reticular layers and contains skin appendages. The subcutaneous tissue, together with adipose tissue, shapes the integument and connects the dermis to deeper structures such as tendons, muscles, and bones.

Skin appendages located within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue include hair follicles, eccrine and apocrine sweat glands, sebaceous glands, as well as blood and lymphatic vessels and nerve endings. The neural network is situated in the dermis; cutaneous vascularization includes arterial–venous and lymphatic components. In addition, the skin surface is covered by a lipid film and desquamated epidermal cells.

Functions of the Skin

Human skin performs multiple physiological functions. Most notably, it protects internal organs from harmful environmental factors—physical, chemical, and microbiological—and helps maintain homeostasis between the organism and its surroundings. Key functions include barrier protection, thermoregulation, participation in water balance and secretion, involvement in the synthesis of certain proteins and compounds, and contributions to protein, lipid, and carbohydrate metabolism. The skin also plays an important role in immune responses and sensory signal transmission. Healthy skin remains intact, tolerates changes in temperature and humidity, and responds appropriately to most skincare products.

Exposome: Factors Affecting Skin Condition

The exposome is a relatively recent concept in dermatological research, referring to the totality of factors influencing the condition and function of human skin. In practical terms, it encompasses daily exposures and is commonly divided into three categories:

A. Internal: including metabolism, hormone levels, body composition, physical activity, gut microbiota, inflammatory states, oxidative stress, and aging.

B. External general: such as stress, climate, and living environment (urban vs. rural).

C. External specific: including chemical and environmental pollutants, infectious agents, radioactivity, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, occupational exposures, diet, and sleep deprivation.

Notably, a substantial proportion of factors impairing skin condition is associated with lifestyle, including chronic stress, UV exposure, inadequate sleep, poor diet, smog, smoking, and alcohol intake.

Scar Formation

Scar formation typically proceeds through three principal phases:

Inflammatory (exudative) phase: The immediate response to injury involves bleeding and clot formation. The clot functions as a natural dressing, protecting the wound from contamination and excessive water loss and providing a matrix under which healing occurs. Inflammation initiates immune activity and regenerative processes. Growth factors are activated, stimulating new tissue formation. This phase lasts several days and culminates in wound cleansing, during which macrophages remove microorganisms and necrotic cells.

Proliferative phase: This phase involves granulation tissue formation and rapid cellular proliferation. New cells form at the injury site. Collagen—the principal protein of connective tissue—is produced, marking the onset of scar development. New blood vessels and supportive cells also form, strengthening the injured tissue.

Scar maturation phase: This phase comprises comprehensive remodeling and progressive dehydration of the wound area. Collagen fibers condense and organize to form the structural basis of the scar. The scar becomes epithelialized, and the tissue gradually gains mechanical resistance. Approximately two months after injury, with normal healing, scar tissue may reach ~80% of the tensile strength of previously healthy skin. However, maturation can continue for several years, during which the scar remodels and changes appearance—typically becoming flatter, lighter, and more elastic.

Types of Scars

Scars can be classified according to different criteria:

A. By time of development:

Immature scars are often erythematous and slightly raised; over time they tend to flatten and may cause pruritus or pain.

B. By morphology:

Hypertrophic scars arise from prolonged healing; they remain confined to the wound margins, are red, thickened, and elevated.

Atrophic scars result from collagen fiber degradation; they are typically round and depressed (e.g., striae and acne scars).

Keloids extend beyond the original wound borders and do not regress spontaneously.

C. By etiology:

Post-surgical scars remain within the limits of the original incision.

Burn scars are often extensive, raised, and may be pruritic or painful; management is complex and time-consuming.

Post-acne scars commonly occur on the face and are frequently atrophic; their size depends on acne severity and healing dynamics.

Traumatic scars are common in children and physically active individuals.

The Impact of NL-GHK-Cu on Scars

The copper tripeptide NL-GHK-Cu is useful not only in primary wound management but also in tissue remodeling—i.e., restoring normal structure and function to damaged tissue. It supports keratinocyte migration and physiologic collagen synthesis, improves skin thickness, elasticity, and firmness, and enhances the appearance of wrinkles, photoaging changes, and hyperpigmentation. It also contributes to skin brightening and supports proteins involved in the protective barrier.

In addition, scarring processes may be attenuated, and—through direct effects on fibroblasts—protein synthesis is increased. NL-GHK-Cu stimulates active, multidimensional remodeling of the extracellular matrix in the skin and subcutaneous tissue, improving elasticity and structural stability with a clinically visible effect on cutaneous resilience. These properties enable NL-GHK-Cu to reduce—and in some cases markedly diminish—scars of various etiologies, while also supporting prophylaxis by limiting the likelihood of new scar formation.

References

- Przewłocka-Gągała M. Contemporary management models for scars in cosmetology and aesthetic medicine. Aesth Cosmetol Med. 2021;10(1):39–47.

- Newton V, Bradley R, Seroul P, Cherel M. Novel approaches to characterize age-related remodeling of the dermal-epidermal junction in 2D, 3D and in vivo. Skin Res. 2017;23:131–148.

- Amano S. Characterization and mechanisms of photoageing-related changes in skin: damages of basement membrane and dermal structures. 2016;25:14–19.

NL-Epithalon as a peptide that improves and maintains the functioning of the circulatory system

Peptide therapy with NL-GHK-Cu in eliminating hair loss and weakening