NL-Epithalon peptide therapy helps maintain proper blood flow within the body; consequently, it is particularly useful in supporting the maintenance of normal blood pressure.

Abstract: Diseases of the circulatory system are currently the most common cause of death in Poland. Many of these conditions develop silently over a prolonged period, and by the time the first symptoms become apparent, it is often too late to implement effective treatment. Modern therapy with the NL-Epithalon peptide may help restore normal blood pressure and, in doing so, support the proper functioning of the circulatory system.

Keywords: NL-Epithalon; cardiovascular system; heart anatomy; cardiac function; blood vessel structure; blood circulation; cardiovascular diseases; cardiotoxicity; fibrinogen suppression; vein; artery; bloodstream

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases comprise a group of disorders affecting the heart and blood vessels. One of the most important risk factors for heart disease is arterial hypertension. The action of the NL-Epithalon peptide may help restore and regulate normal blood pressure in the body, thereby supporting better physical condition and limiting the progression of many diseases and symptoms that arise as consequences of cardiovascular dysfunction.

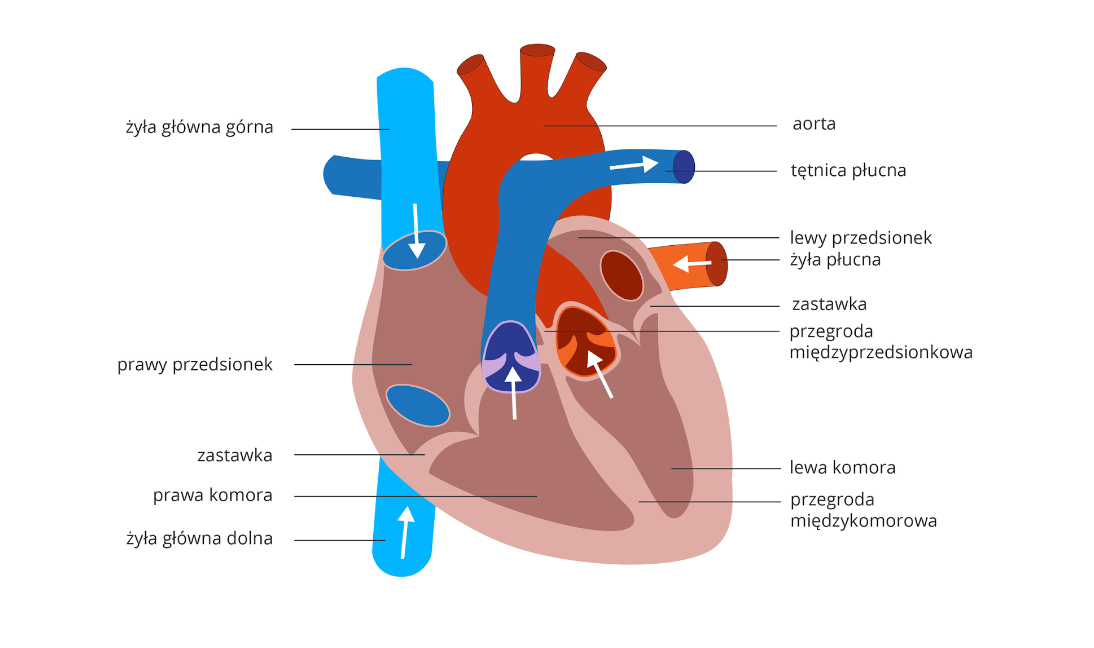

The Circulatory System

The circulatory system, as a closed transport network for blood, consists of the heart and blood vessels. The central component is the heart, located in the mediastinum behind the sternum. It is composed of striated cardiac muscle tissue, whose contractions drive blood through the vessels. The heart consists of two atria and two ventricles (right and left). Because the atria pump blood only into the ventricles, their walls are thinner than those of the ventricles, which pump blood into all arteries. For blood to reach even the most distant cells, pressure must be sufficiently high. Veins deliver blood into the atria, and arteries carry blood away from the ventricles. Valves located between the atria and ventricles, and at the outflow of the ventricles, open in only one direction, enforcing unidirectional blood flow and preventing backflow.

Cardiac Function

The heartbeat is a continuous process, because interruption of blood supply to any organ results in irreversible and dangerous changes, including tissue death. Venous blood first enters both atria; when they contract, blood is pushed into the ventricles. Ventricular contraction then ejects blood from the heart into the arteries. After this phase, the heart briefly rests; during relaxation, the atria refill with blood.

Blood Vessel Structure

Blood is distributed throughout the body via blood vessels—arteries, veins, and capillaries. The outer layer of a vessel serves a protective function; the middle layer is composed of smooth muscle, allowing vessels to constrict or dilate and thereby regulate blood flow; and the inner layer is thin and smooth to ensure unobstructed blood flow. Blood in arteries flows under high pressure, which is why the muscular layer and inner lining are relatively thick. In contrast, venous smooth muscle is thinner due to lower pressure. The inner venous layer forms valves that prevent backflow and assist venous return against gravity. Between arteries and veins are very thin capillaries forming dense networks. Capillary walls consist of a single layer of cells (simple squamous epithelium), enabling gas exchange and the movement of various substances into and out of these vessels.

Blood Circulation in the Bloodstream

Blood flow is possible due to a closed system comprising two circuits: the pulmonary (small) and systemic (large) circulations. In the pulmonary circulation, blood rich in carbon dioxide and relatively low in oxygen is pumped from the right ventricle into the pulmonary arteries. These branch into smaller arterioles and ultimately into capillaries surrounding the alveoli. Gas exchange occurs between capillary blood and alveoli: carbon dioxide diffuses out of the blood and oxygen diffuses into it. Oxygenated blood returns via venous capillaries that merge into larger veins; pulmonary veins carry oxygen-rich blood into the left atrium. When the left atrium contracts, blood enters the left ventricle, initiating systemic circulation. From the left ventricle, blood flows into the aorta, which branches into smaller arteries and then into capillary networks near body cells. These networks deliver oxygen and nutrients and remove metabolic waste. Internal gas exchange then occurs: oxygen diffuses into tissues, while carbon dioxide diffuses into capillaries. Deoxygenated blood collects into venous capillaries and then into larger veins. The superior and inferior venae cavae return carbon dioxide–rich blood to the right atrium.

Regulation of Aortic Blood Pressure and Measurement of Arterial Pressure

In systemic arteries, pressure is high due to thick, tense walls and because blood is ejected into them by the left ventricle during systole. During ventricular diastole, after closure of the aortic valve, pressure would theoretically fall to zero; however, in a healthy resting individual arterial pressure is approximately 120/80 mmHg—meaning it does not exceed 120 mmHg and does not fall below 80 mmHg. This occurs because the aortic wall is elastic, composed of both smooth muscle and elastic fibers. The aorta stretches as it receives blood from the left ventricle, and during diastole it recoils, exerting pressure on the blood volume within its lumen and propelling it toward the periphery. As a result, peripheral blood flow is continuous rather than intermittent.

The Role of Resistance Arterioles in Regulating Blood Flow

As arteries branch, their elasticity decreases and their walls become predominantly smooth muscle, while blood flow velocity increases and arterial pressure gradually falls. The arterial system terminates in arterioles, where the pressure drop is particularly pronounced—especially when some arterioles constrict completely, preventing blood from passing onward into capillaries. For this reason, arterioles are often referred to as “resistance vessels.” Resistance vessels alternate between constriction and dilation, because if all constricted simultaneously, arterial pressure would drop to extremely low values. This phenomenon can be observed, for example, in anaphylactic shock, where circulating blood volume may be normal but arterial pressure can become unmeasurable due to profound paralysis of resistance vessels.

Normal Arterial Blood Pressure

Based on epidemiological studies, the threshold distinguishing normal from elevated blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg. Above this level, the risk of target-organ complications increases significantly—such as coronary artery disease or stroke. Detailed analyses of the relationship between blood pressure and complications indicate that risk decreases further when blood pressure values are lower. The concept of optimal blood pressure refers to values not exceeding 120/80 mmHg.

Arterial Hypertension

Arterial hypertension is a clinical condition defined by elevated blood pressure—i.e., arterial pressure of 140/90 mmHg or higher. Diagnosis is based on repeated measurements performed over intervals of days or weeks; hypertension should not be diagnosed on the basis of a single reading. In most patients, no single specific cause is identified. Blood pressure elevation may be influenced by multiple factors, including genetic predisposition, obesity, high salt intake, aging, psychological factors (including chronic stress), and an unhealthy lifestyle characterized by low physical activity and sedentary behavior.

Hypotension

Arterial hypotension (hypotonia) is a circulatory disorder that may cause symptoms involving various organs. Hypotension is typically defined when systolic blood pressure in an adult falls below approximately 100–105 mmHg; this threshold is approximate and does not account for factors such as sex, age, or genetic predisposition. Hypotension does not always indicate serious disease. It most commonly occurs in individuals who exercise regularly and intensely, and in slender women. It can affect all age groups, but often appears in adolescents with low body weight. In general, humans are born with low blood pressure that rises with age—though sometimes insufficiently. Although hypotension is not as dangerous as hypertension, it should not be ignored, because a sudden drop in blood pressure may lead to loss of consciousness, for example while operating a vehicle.

The Impact of NL-Epithalon on Arterial Hypertension

One of the most common lipid abnormalities associated with arterial hypertension is hypercholesterolemia, largely due to its prevalence in the general population; however, atherogenic dyslipidemia is more characteristic, particularly in patients with hyperinsulinemia. Atherogenic dyslipidemia is defined by increased triglyceride levels and reduced HDL cholesterol. The coexistence of hypertension and lipid abnormalities strongly supports the need to measure blood lipid concentrations in every case of hypertension and to implement appropriate management. Studies indicate that individuals using modern NL-Epithalon therapy may demonstrate improved—and, importantly, normalized—lipid metabolism, which in turn may contribute to a reduction in arterial hypertension and thereby lower the overall risk of cardiovascular diseases and related complications.

References

- Apostolopoulos V, Bojarska J, Chai TT, et al. A Global Review on Short Peptides: Frontiers and Perspectives. Molecules. 2021;26(2):430. Published 2021 Jan 15. doi:10.3390/molecules26020430

- Adult Treatment Panel III. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497

Regenerative properties of the NL-GHK-Cu peptide for the skin

Peptide therapy with NL-GHK-Cu in eliminating hair loss and weakening