Amino acids of varying chain lengths and sequences can form dimers and polymers. Depending on the number of amino acid residues located on the polymer chain, polymers are divided into peptides and proteins. Peptides contain approximately 50 amino acids in their structure, while proteins contain a larger number of amino acid residues than peptides in one or more chains. Amino acids, proteins, and peptides all play a crucial role in the proper functioning of the body. Modern peptide therapies can enable the body to regenerate.

Keywords: peptide · amino acid · protein · α helix · β structure · nonpolar chain · alanine · valine · leucine · isoleucine · phenylalanine · tryptophan · methionine · proline · glycine · serine · threonine · tyrosine · cysteine · asparagine · glutamine · aspartic acid · glutamic acid · configuration · conformation · dipeptide · oligopeptide · peptide bond · growth hormone Abbreviations: ACTH- adrenocorticotropin; CRH- corticoliberin; POMC- proopiomelanocortin; MMC- migrating motor complex; GRPP- glicentin-dependent pancreatic polypeptide; HGH - Growth Hormone.

The biological role of amino acids, proteins, and peptides in the proper functioning and regeneration of the body, presented below, will allow you to familiarize yourself with their effects and the possibilities they offer.

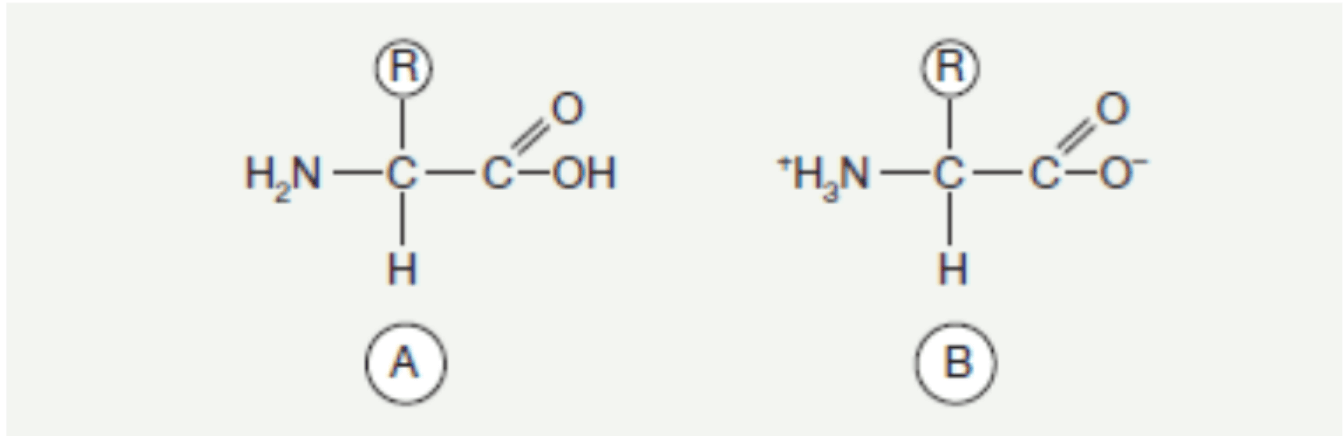

Amino acids, among the best-known components of living organisms, occur as derivatives of organic acids, where at least one hydrogen atom is replaced by an amino group. They are ubiquitous components, occurring both free and bound—in the case of peptides and proteins. Each amino acid found in proteins, with the exception of proline and hydroxyproline, has an amino group located on the α-carbon and an R side chain, which can have different structures and is connected by the same carbon atom.

Fig. 1. General formula of an amino acid. A. In free form B. In zwitterionic form.

Approximately 300 amino acids are known in the environment, but 22 are commonly found, of which 2 additional ones have been relatively recently discovered and occur only in certain proteins. The presence and location of the known amino acids in the protein structure are determined by genetic properties; in some cases, this results from post-translational modification of amino acid residues that were previously incorporated into the polypeptide chain. The remaining amino acids may exist in free form or in non-protein compounds.

The role of an amino acid in a protein is determined by the structure of its side chain (R-group), which defines the classification of amino acids into several groups based on the nature of their side chains.

Classification of Amino Acids

Amino Acids with Nonpolar Side Chains

This group includes: alanine, valine, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, methionine, proline, and glycine.

In the case of the last two mentioned amino acids, a certain peculiarity exists. Proline, as an unusual example, does not have an $\alpha$-amino group but an imino group, which is built into the pyrrolidine ring structure. Glycine, on the other hand, lacks a side chain, which is replaced by a hydrogen atom.

Each of the listed amino acids possesses a nonpolar side chain that is unable to acquire or lose protons and does not participate in the formation of hydrogen or ionic bonds. The side chain is usually considered lipophilic or hydrophobic (water-avoiding). Such chains shun the aqueous environment by clustering together and are directed towards the interior of the protein molecule. When in an aqueous environment, their behavior is best compared to that of oil droplets, merging into larger drops, thereby reducing contact with water.

Fig. 2. Amino acids with nonpolar side chains.

Amino Acids with Polar Uncharged Side Chains

This group includes: serine, threonine, tyrosine, cysteine, asparagine, and glutamine.

These amino acids have a zero charge at neutral pH, but cysteine and tyrosine can lose a proton at alkaline pH. Serine, threonine, and tyrosine are capable of forming hydrogen bonds due to the presence of a polar hydroxyl group. Hydrogen bonds can also be formed by the side chains of asparagine and glutamine because of their carbonyl and amide groups. The amide group of asparagine, as well as the hydroxyl groups of serine and threonine, can be sites for sugar component binding.

Fig. 3. Amino acids with polar uncharged side chains.

Amino Acids with Acidic Side Chains

Fig. 3. Amino acids with acidic side chains.

The group of amino acids with acidic side chains includes aspartic acid and glutamic acid. The side chains of these amino acids contain carboxyl groups. In a neutral pH environment, they undergo complete dissociation, becoming negatively charged carriers. The fully ionized forms of aspartic acid and glutamic acid are called aspartate and glutamate. The resulting, modified names after ionization indicate that they are anions in an environment of physiological pH.

Amino Acids with Basic Side Chains

Fig. 4. Amino acids with basic side chains.

The group of amino acids with basic side chains includes lysine, arginine, and histidine. The side chains of these amino acids contain groups capable of binding protons. These groups are the $\epsilon$-amino group of lysine, the guanidinium group of arginine, and the imidazole ring of histidine. At physiological pH, the R-groups of lysine and arginine are fully ionized, thereby acquiring a positive charge. The free amino acid histidine has a slightly basic character, existing in the environment in a neutral form at physiological pH. However, it may happen that histidine in a protein has an R-group that is positively charged or neutral, depending on the environment created by the protein. This plays a crucial role in the function of the protein hemoglobin.

Proteins

Characterization of Proteins

Proteins, as condensation polymers of amino acids, are numerous in the human body and are a fundamental structural component for its proper functioning. Those built exclusively from amino acid residues are called simple proteins or holoproteins. Complex proteins (proteids) additionally contain a prosthetic group which is a non-protein component.

As macromolecules, they are formed through the interaction of the $\alpha$-carboxyl group of one amino acid with the $\alpha$-amino group of another, creating a peptide bond. Proteins with a molecular weight greater than 10,000 daltons (Da) are called polypeptides. All proteins with a lower molecular weight are defined as oligopeptides. Every protein has a polypeptide chain consisting of 100 to 1,000 amino acid residues.

Fig. 5. General formula of simple proteins (holoproteins).

Primary Structure

The primary structure of a protein's polypeptide chain defines the sequence in which amino acid residues are connected. Individual amino acids are covalently linked by peptide bonds. Only specific amino acid sequences occur in proteins due to the vast possibility of combinations. The distribution of amino acid residues along the polypeptide chain is not strictly defined. Amino acids with acidic or basic side chains or those containing aromatic rings in their structure most often occur in clusters, meaning several amino acid residues may appear next to each other.

The importance of the primary structure can be illustrated by the example of the protein hemoglobin. In this case, replacing a single amino acid with another subsequently leads to the formation of pathological hemoglobin. To better understand its significance, for instance, at the sixth position, glutamate is replaced by another amino acid (valine or lysine), which leads to negative biological consequences. Red blood cells undergo a biologically altered state, leading to an atypical shape. The red blood cells become susceptible to hemolysis, which simultaneously reduces the number of erythrocytes in the blood. The breakdown products of erythrocytes are captured by the liver and spleen, and the concentration of the bile pigment bilirubin is increased as a result of heme breakdown in hemoglobin. These processes lead to the development of the disease state known as hemolytic anemia.

Secondary Structure

When discussing the secondary structure, the key terms are configuration and conformation. While configuration refers to the geometric relationship between specific sets of atoms (e.g., the transformation of D-alanine into L-arginine, achieved by breaking and reforming covalent bonds), conformation refers to the spatial arrangement of the protein. Conformation does not involve the breaking of covalent bonds but the breaking and reforming of non-covalent forces, such as hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic interactions. Only some resulting conformations have biological significance.

The most common form of a protein's secondary structure is the $\alpha$-helix in a spiral shape. There are 3.6 amino acid residues per turn of the $\alpha$-helix. This specific, distinct spiral form allows for the formation of maximum-strength intramolecular and inter-turn hydrogen bonds due to electrostatic interactions. The $\alpha$-helix structure, involving the polypeptide chain's peptide bond, permits its participation in hydrogen bonding, with the exception of bonds involving the imino groups of proline. Polypeptides synthesized from L-amino acids or D-amino acids spontaneously form the $\alpha$-helix structure. Polypeptides formed from amino acid racemates and polymers of certain amino acids, such as proline or hydroxyproline, are unable to spontaneously form this structure.

For example, $\alpha$-keratin, a protein found in hair, among other places, is almost entirely covered by the $\alpha$-helix structure, while collagen and elastin, which contain the aforementioned proline and hydroxyproline, have no ability to form this structure.

The second known form of protein secondary structure is the $\beta$-sheet, also known as the $\beta$-pleated sheet. The formation of the $\beta$-sheet involves two or more polypeptide chains. The structure can be parallel, where the amino and carboxyl termini of the chains run in the same direction, or antiparallel, where these ends are directed in opposite directions.

The polypeptide chain in the $\beta$-structure is more axially extended than the $\alpha$-helix chain, and bends are formed on its surface. These bends reverse the direction of the molecule's long axis and enable the polypeptide chain to be packed into a compact globular form. Proline, glycine, and amino acids with electrically charged side chains often occur in these bends.

Tertiary Structure

The tertiary structure preserves the secondary structure while allowing for the three-dimensional folding of the protein molecule. The spatial packing of the protein molecule is primarily dictated by the primary structure and, indirectly, the secondary structure.

The tertiary structure is stabilized by interactions between the side chains of amino acid residues, including covalent bonds (such as disulfide bridges) and low-energy non-covalent bonds (like hydrogen bonds). In aqueous solutions, the structure of globular proteins is compact. Hydrophobic side chains of amino acid residues are hidden inside the molecule, while hydrophilic groups are located on the surface. Polar groups, including those hidden inside the molecule, along with the components of the peptide bonds, allow for the formation of hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions. The tertiary structure only forms when bonds exist that allow for the connection of linearly distant amino acid residues.

Quaternary Structure

The last of the presented structures occurs only in some proteins and defines the spatial arrangement and subunit composition with respect to a single protein molecule. In this case, proteins have a high molecular weight and consist of two or more monomers (polypeptide chains).

Usually, in the quaternary structure, the protein elements involved in its formation are joined by low-energy hydrogen bonds. In some cases, the structure is stabilized by disulfide bridges between cysteine residues. In the case of collagen and elastin, the covalent bonds between subunits are exceptionally stable.

The biological properties of the quaternary structure can be modified by small-molecule substances called allosteric effectors. The quaternary structure is very well understood in the case of hemoglobin and enzymatic proteins, particularly lactate dehydrogenase.

Peptides

Characterization of Peptides

Peptides are chemical compounds built, similarly to proteins, from amino acids. They are a subject of wide interest, performing important biological functions. Many hormones and neurotransmitters are peptides. Endogenous peptides exhibit antimicrobial activity, acting as a defense system for the body.

Naturally occurring peptides and their synthetic analogues are considered attractive compounds of therapeutic significance due to their high activity, low toxicity, and lack of drug interactions. In medical practice, only a few peptides are used because of their biological instability and rapid degradation; however, peptide synthesis allows for the production of stable forms. The same applies to the synthesis of peptides from natural sources, which are used, among other things, in vaccine production.

The product formed from the reaction of two amino acids is called a dipeptide, retaining the free amino group of one amino acid and the free carboxyl group of the second. Peptides composed of several to a dozen amino acids are referred to as oligopeptides, while longer peptides, containing dozens of amino acid residues, are called polypeptides.

The nomenclature of peptides begins with the name of the N-terminal amino acid residue, followed by the names of the subsequent amino acid residues, and ends with the name of the C-terminal amino acid. The sequence of amino acids is written using three-letter or one-letter symbols. Peptides occur in an unbranched form, possessing only two specific ends. One is called the amino terminus (N-terminus), where the amino acid with a free $\alpha$-amino group is located. The other is called the carboxyl terminus (C-terminus), where the amino acid with a free $\alpha$-carboxyl group is located.

Peptide Bond

The carbon of the $\alpha$-carboxyl group bonds with the nitrogen of the $\alpha$-amino group through a single bond, the peptide bond. It is assumed that this bond exists in the form of two structures that remain in a specific equilibrium with each other. The C-N bond converts to C=N and vice versa. Rotation around the C=N axis is not possible, making the peptide bond rigid enough to possess double-bond characteristics.

Fig. 6. Formation of a peptide bond.

In the case of a peptide bond involving the imino group of proline or hydroxyproline with the carboxyl group of another amino acid, a different, distinct structure is formed. In this case, the nitrogen is incorporated into the pyrrolidine ring structure, and there is no hydrogen substituent, thus preventing rotation around the bonds formed in the presence of nitrogen.

Amino acids involved in peptide bond formation lose molecular fragments: the -OH from the carboxyl group and the -H from the amino group. This is why amino acids found in peptides and proteins are called amino acid residues. The resulting peptide bonds are stable, and their breakdown can only occur under the action of strong bases and acids at simultaneously high temperatures.

Biologically Active Peptides

Peptide hormones and protein hormones are widespread in the surrounding environment. They were previously mostly known as less stable forms. Peptide synthesis increasingly allows for the selection of peptide therapy that will be effective and lasting, depending on the body's needs.

An example of a biologically active peptide is glutathione, which is a tripeptide with a specific structure built from glutamate, cysteine, and glycine. Glutamate is the N-terminal amino acid. However, the linkage between glutamate and cysteine is atypical for peptides and proteins, as it involves the $\gamma$-carboxyl group of glutamate, not the $\alpha$-carboxyl group.

Glutathione exists in reduced and oxidized forms, being $\gamma$-glutamylcysteinylglycine. In the reduced form, it has a free sulfhydryl group (-SH), and in the oxidized form, a pair of hydrogen atoms is detached from the -SH groups. The sulfur atoms are left without hydrogen, resulting in the formation of a disulfide bridge. Glutathione's ability to switch between oxidized and reduced states is crucial in oxidation-reduction processes.

Another example is oxytocin and vasopressin, which are nanopeptides produced by hypothalamic neurons and released by the posterior pituitary lobe, differing only by two amino acids. Cysteine occurs in two positions, leading to the formation of a disulfide bridge. Oxytocin acts as a hormone that stimulates uterine contractions. Vasopressin stimulates water reabsorption in the renal tubules. Vasopressin also plays a key role in regulating the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) during stress situations.

Peptide Hormones

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH)

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) is a 39-amino-acid peptide formed as a result of the degradation of the much larger precursor molecule, proopiomelanocortin (POMC). Proopiomelanocortin is also the source of other active peptides. Two peptides are contained within the ACTH structure: $\alpha$-melanocyte-stimulating hormone ($\alpha$-MSH), which is structurally identical to the first 13 amino acids of ACTH, and a corticotropin-like intermediate lobe peptide (fragment 18-39 of ACTH).

The primary function of ACTH is to stimulate the adrenal cortex so that it can secrete steroid hormones. ACTH is responsible for regulating activity at the zona fasciculata and zona reticularis levels. The first 18 amino acids are responsible for the biological activity of ACTH. ACTH regulation occurs through corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), a hypothalamic hormone, which releases corticotropin, and through cortisol via a negative feedback loop. This means that a cortisol deficiency stimulates CRH and ACTH, while an excess inhibits this secretion. By releasing cortisol, many essential life functions are regulated, including mobilizing the body for stress conditions, raising blood pressure, and anti-inflammatory capabilities. ACTH is secreted pulsatilely in a circadian rhythm, with its highest concentration observed in the morning hours when it is most desirable, and then decreasing throughout the day. Increased ACTH secretion is observed in disease states such as adrenal insufficiency, Cushing's disease, and Nelson's syndrome.

Insulin and C-Peptide

Insulin and C-peptide are continuously secreted by the pancreas in the human body. C-peptide is produced during the biosynthesis of insulin. Pancreatic cells initially produce preproinsulin, which undergoes further modification by the cleavage of amino acids, leading to proinsulin, composed of two chains (A and B) linked by C-peptide. C-peptide is then cleaved from proinsulin, resulting in the final form of insulin. When glucose appears in the body, the pancreas receives a signal to release granules containing the stored insulin and C-peptide molecule.

C-peptide is retained in the liver much longer than insulin because it is not degraded there. Its breakdown occurs mainly in the kidneys. For both insulin and C-peptide, elevated or excessively low concentrations lead to the development of Type I or Type II diabetes, as well as Cushing's disease. Fluctuations in C-peptide concentration may also indicate chronic kidney failure or the presence of metastases or local tumor recurrence, which is why maintaining their correct concentration norms is so important.

Motilin

Motilin is a hormone associated with the smooth muscles of the stomach and intestines, controlled by the vagus nerve fibers. It is synthesized in endocrine cells. As a peptide hormone composed of 22 amino acids located in a specific sequence, it is produced by cells in the small intestine. Produced by the endocrine cells of the digestive system (M cells), it participates in regulating gastrointestinal motility.

Motilin is a crucial hormone involved in the formation of Phase III of the Migrating Motor Complex (MMC), in which the stomach and small intestine are tasked with emptying the stomach of unnecessary food residues and exfoliated epithelial cells by stimulating peristaltic movements. The hormone additionally influences gallbladder emptying during the interdigestive period when motilin concentration is highest.

Glucagon

Glucagon is one of the hormones involved in regulating glucose concentration. This peptide is secreted by the endocrine cells of the pancreas. It is a polypeptide composed of 29 amino acids, derived from a precursor structure of 180 amino acids. Changes in glucose concentration allow for the secretion of glucagon.

The production of the hormone glucagon takes place in the pancreatic islets, where glucagon and glicentin-related pancreatic polypeptide (GRPP) are formed from proglucagon. The main role of glucagon is to maintain the correct serum glucose concentration during drops between meals or during physical exertion. Its stores are released from the liver in such situations to provide the body with adequate protection. Additionally, it may participate in regulating food intake, potentially leading to an earlier feeling of satiety. Glucagon can potentially inhibit ghrelin release and inhibit intestinal peristalsis.

Protein Hormones

Human Growth Hormone (HGH)

Human Growth Hormone (HGH) is also called somatotropin. It is produced by acidophilic cells belonging to the anterior pituitary lobe. The hormone leads to increased proliferation of cells in various tissues, resulting in an increase in their number and size. HGH consists of 190 amino acids in the form of a simple polypeptide chain.

It is released pulsatilely in the body approximately every 3-4 hours, with its highest concentrations recorded at night. The hormone's secretion process is regulated by hypothalamic hormones with opposing actions: Growth Hormone-Releasing Hormone (GHRH) and Somatostatin (SRIF), which inhibits its release.

The release of somatotropin is regulated by neurohormones: somatoliberin (GHRH), somatostatin (GHIH), ghrelin, glucocorticosteroids, fatty acids, glucose, insulin, and sex hormones. Growth hormone regulates metabolic processes, modulates body growth, and stimulates cell proliferation. HGH has a wide range of effects, including stimulating long bone growth, synthesizing nucleic acids, and regulating carbohydrate metabolism.

Growth hormone has broad applications among athletes. Administering somatotropin to athletes contributes to strengthening, muscle building, and minimizing injuries during training by developing connective tissue that forms cartilage. When deciding to take growth hormone, maintaining other factors, such as sufficient sleep and an appropriate diet, is also important.

Conclusions

As mentioned above, amino acids, proteins, and peptides participate in the proper functioning of the body. In the case of peptides, it can be concluded that their skillful use allows for a safe, effective, and satisfactory health therapy. Given their action, they are indicated for use in almost all cases and for all individuals. They are especially recommended for athletes for regenerative and preventive purposes. Deficiencies of both protein and peptide hormones can lead to serious functional disorders in the body.

BPC-157 Product of the Year 2020! Innovation comes first!

Neuroprotective and Antidepressant Effects of BPC-157. Influence of BPC-157 on Brain Function.